Research

Here is a list of various research projects that I have worked on, or am currently working on:

-

Natural language without semiosis

- here are some slides from a recent presentation (email me for further details)

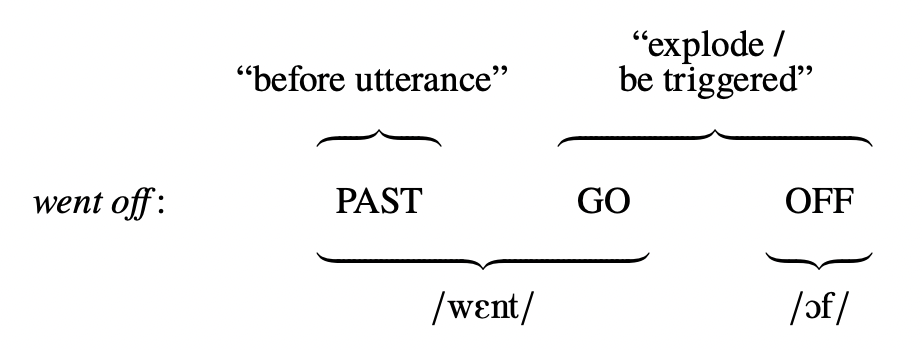

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@unpublished{Preminger:2022, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Note = {{Ms.}}, Title = {Natural language without semiosis}, Year = {in prep.}}The last few decades have borne witness to a toppling of the lexicalist paradigm as it concerns the mapping between syntax and morphology. At the same time, work on the syntax-semantics mapping has remained largely ensnared in lexicalist thinking. My goal here is to provide arguments for, and an implementation of, a symmetrically non‑lexicalist model for syntax at both its interfaces, with form (PF) and with meaning (LF). This is a model where individual syntactic nodes, in the general case, need not map onto a form or a meaning. Instead, syntax is mapped to the interfaces via PF‑formatives and LF‑formatives. A PF‑formative is a rule that spells out a contiguous piece of syntactic structure (which may consist of a single node or more) to the morpho-phonology. An LF‑formative is a rule that spells out a contiguous piece of syntactic structure (which, again, may consist of a single node or more) to the semantics. This way of characterizing the mappings to PF and LF predicts that we should find cases where the nodes spelled out using a given PF‑formative and those spelled out using a given LF‑formative stand in a relation of partial overlap. And this prediction is borne out. Consider, for example, an expression like went off (in the sense of "exploded" or "was triggered"). Here, there is an LF‑formative (not decomposable into the meanings of its parts) consisting of GO and OFF, and a PF‑formative (not decomposable into the forms of its parts) consisting of PAST and GO. As shown below, these formatives stand in exactly the kind of partial-overlap relation just mentioned. Crucially, the PF contribution of OFF and the LF contribution of PAST in this case are still their run-of-the-mill respective contributions: the trivial, single-terminal PF‑formative associated with OFF (since off does not exhibit any contextual allomorphy here), and the trivial, single-terminal LF‑formative associated with PAST (since the past tense does not exhibit any contextual allosemy here). Cases of this sort provide the basis for a broader architectural claim: individual syntactic atoms have neither form nor meaning, nor are they directly associated with forms or meanings. Instead, they are mapped onto forms and meanings via PF‑ and LF‑formatives. As we have seen, some formatives can be trivial (mapping a single syntactic terminal to the relevant interface), while others can involve multiple syntactic nodes at once.

On this view, we might also expect to see syntactic nodes for which there is simply no trivial PF‑formative available, and ones for which there is simply no trivial LF‑formative available. Such nodes could only be mapped to the relevant interface if they happened to occur in the right context, namely, a context for which an appropriate non‑trivial formative were available. This is indeed attested. There is no LF‑formative, for example, whose insertion context is the node FANGLE (which can be found in the expression newfangled). Instead, there is only the LF‑formative whose insertion context consists of NEW, FANGLE, and PARTICIPIAL. Conversely, there is a PF‑formative in English whose insertion context consists of NONPAST and MUST, but no PF‑formative consisting of MUST alone (*to must; compare: to have to).

Because syntactic atoms are merely the building blocks from which the insertion contexts of PF- and LF‑formatives are constructed, and are not themselves "interpreted" or "pronounced", this proposed model can be seen as a final rejection of the semiotic basis upon which the atoms of generative grammar have traditionally been built. I will argue that even those contemporary linguistic frameworks that distance themselves from outright Saussureanism, such as Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz 1993, 1994) and Nanosyntax (Starke 2009, Caha 2009, 2019), retain certain Saussurean vestiges that render them less explanatory than the current proposal.

Cases of this sort provide the basis for a broader architectural claim: individual syntactic atoms have neither form nor meaning, nor are they directly associated with forms or meanings. Instead, they are mapped onto forms and meanings via PF‑ and LF‑formatives. As we have seen, some formatives can be trivial (mapping a single syntactic terminal to the relevant interface), while others can involve multiple syntactic nodes at once.

On this view, we might also expect to see syntactic nodes for which there is simply no trivial PF‑formative available, and ones for which there is simply no trivial LF‑formative available. Such nodes could only be mapped to the relevant interface if they happened to occur in the right context, namely, a context for which an appropriate non‑trivial formative were available. This is indeed attested. There is no LF‑formative, for example, whose insertion context is the node FANGLE (which can be found in the expression newfangled). Instead, there is only the LF‑formative whose insertion context consists of NEW, FANGLE, and PARTICIPIAL. Conversely, there is a PF‑formative in English whose insertion context consists of NONPAST and MUST, but no PF‑formative consisting of MUST alone (*to must; compare: to have to).

Because syntactic atoms are merely the building blocks from which the insertion contexts of PF- and LF‑formatives are constructed, and are not themselves "interpreted" or "pronounced", this proposed model can be seen as a final rejection of the semiotic basis upon which the atoms of generative grammar have traditionally been built. I will argue that even those contemporary linguistic frameworks that distance themselves from outright Saussureanism, such as Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz 1993, 1994) and Nanosyntax (Starke 2009, Caha 2009, 2019), retain certain Saussurean vestiges that render them less explanatory than the current proposal.

-

The Anaphor Agreement Effect: further evidence against binding-as-agreement

- download manuscript

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@unpublished{Preminger:2019, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Note = {{Ms.}}, Title = {The {Anaphor} {Agreement} {Effect}: further evidence against binding-as-agreement}, Url = {https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004401}, Year = {2019}}The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE), originally formulated by Rizzi (1990) as a ban against the occurrence of anaphors in agreeing positions, seems to suggest a rather tight interaction between syntactic agreement in phi-features (person, number, and gender) on the one hand, and binding on the other. This has led to work that takes the AAE as support for theories where syntactic phi-agreement is a necessary condition for binding, theories that will be referred to here as reductionist (e.g. Reuland 2011). The basic idea in such work is that anaphors are, by their very nature, deficient or underspecified with respect to phi-features, and therefore an phi-agreement probe seeking to establish a syntactic relationship with an anaphor will not come upon a fully-fledged, valued set of phi-features. I show that upon closer inspection, the AAE in particular and anaphoric binding more generally provide fairly strong evidence against reductionist theories. That is because such theories require, somewhat paradoxically, assumptions about phi-agreement and about the structure of reflexive anaphors which break their compatibility with an agreement-based theory of binding, in the first place. Instead, I propose that the AAE arises because anaphors, universally, adhere to what I call phi-encapsulation: the phi-bearing portion of an anaphor is properly contained in an additional layer of structure, which I label AnaphP. And it is this additional layer (AnaphP), not the phi-bearing layer, that is responsible for the anaphoric behavior of the expression. I argue that AnaphP is typically syntactically opaque to probing for phi-features, and this is what gives rise to the AAE. On the way, I provide arguments against two persistent misconceptions having to do with the AAE in particular and binding in general. First, building on observations by Woolford (1999) and Tucker (2011), I argue that Rizzi's original characterization of the AAE – as a restriction on the possible positions in which anaphors can and cannot occur – has little cross-linguistic merit. The only cross-linguistically viable statement of the AAE is as a ban on nontrivial (i.e., alternating) agreement with reflexive anaphors, not in terms of a restriction on their occurrence. The second misconception has to do with phi-feature matching between binder and bindee, and whether it constitutes an argument for syntactic phi-agreement between the two. I show that it does not. That is because phi-feature matching between binder and bindee is enforced even in instances where no syntactic relation could possibly hold between the two. This includes cases of Donkey Anaphora, cases of cross-utterance (and cross-speaker) anaphora, and cases of linguistically-unanteceded deixis. These all provide evidence for phi-feature matching, even in uninterpreted phi-features like grammatical gender on inanimates, in the absence of any syntactic relation between the matched phrases. Once we come to terms with these facts, it becomes clear that whatever mechanism underpins these non-syntactic cases is also sufficient to ensure phi-matching under anaphoric binding, without implicating syntactic phi-agreement in any way. -

Functional structure in the noun phrase: revisiting Hebrew nominals

- download paper; published in 2020, Glossa 5(1): 68. doi: 10.5334/gjgl.1244

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{Preminger:2020, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.5334/gjgl.1244}, Journal = {Glossa}, Number = {1}, Pages = {68}, Title = {Functional structure in the noun phrase: revisiting {Hebrew} nominals}, Volume = {5}, Year = {2020}}Bruening (2010, 2020) and Bruening, Dinh & Kim (2018) (henceforth BBDK) have recently advanced a series of arguments for the claim that nominal phrases are not headed by a functional projection. These works take particular aim at the DP Hypothesis (Abney 1987; see also Szabolcsi 1983), but their claim is stronger than a mere rejection of that hypothesis. Their claim is that the outermost layer in a nominal phrase is projected by the noun itself, not by any functional structure surrounding the noun. In this paper, I revisit Ritter's (1991) findings and show that BBDK's claims are incompatible with the evidence she adduces from (modern) Hebrew. Ritter's paper takes for granted that DPs exist, and concentrates on how Hebrew nominals motivate the existence of an additional projection in between DP and NP (namely, NumP). What I show here, however, is that if one harbors doubts that there are any functional projections above the projection of the noun, Ritter's work provides clear evidence that such functional projections exist. -

What the PCC tells us about “abstract” agreement, head movement, and locality

- download paper; published in 2019, Glossa 4(1): 13. doi: 10.5334/gjgl.315

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{Preminger:2019, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.5334/gjgl.315}, Journal = {Glossa}, Number = {1}, Pages = {13}, Title = {What the {PCC} tells us about ``abstract'' agreement, head movement, and locality}, Volume = {4}, Year = {2019}}It has become commonplace in syntactic theory to posit feature-valuation relations, such as agreement between a verbal head and a nominal argument, even in cases where there is no associated morpho-phonological covariance. Let us refer to such hypothesized feature-valuation relations, where the assumed exponents are all null, as "abstract" agreement. In the first part of this paper, I use the cross- and intra-linguistic distribution of Person Case Constraint (PCC) effects to argue that natural language does not allow abstract agreement in phi‑features (person, number, and gender/noun-class). Next, I turn my attention to clitic doubling. As far as PCC effects are concerned, clitic doubling behaves as though it were equivalent to overt agreement. In fact, the distribution of the PCC is hard to state unless we collapse the two. This is surprising because, quite simply, clitic doubling is not agreement; it behaves like movement, and unlike agreement, in crucial respects (most notably, in creating new antecedents for binding). Nor can this be because clitic doubling, qua movement, is contingent on prior agreement – since the claim that all DP movement depends on prior agreement is demonstrably false. I propose that clitic doubling necessarily involves a preliminary agreement step because it is an instance of non-local head movement – and movement of X0 to Y0 always requires a prior syntactic relationship between Y0 and XP. In cases of maximally local head movement (à la Travis 1984), this requirement is satisfied by c‑selection. But in non-local cases, it is phi‑agreement that fills this role. Thus, wherever clitic doubling is found, agreement has to have occurred, explaining why the two are interchangeable when it comes to conditioning the PCC. I conclude by discussing the nature of the ban on abstract phi‑agreement. Viewed as a grammatical principle, this ban would require simultaneous reference to syntax and morpho-phonology, mixing information from different grammatical modules into one constraint. Instead, I suggest that this ban is not a grammatical principle at all: it arises as the result of the acquisition strategy learners engage in when it comes to the placement of unvalued phi‑features on functional heads. -

The Agreement Theta Generalization (with Maria Polinsky)

- download paper; published in 2019, Glossa 4(1): 102. doi: 10.5334/gjgl.936

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{PolinskyPreminger:2019, Author = {Polinsky, Maria and Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.5334/gjgl.936}, Journal = {Glossa}, Number = {1}, Pages = {102}, Title = {The {{\em{{Agreement} {Theta} {Generalization}}}}}, Volume = {4}, Year = {2019}}In this squib, we propose a new generalization concerning the structural relationship between theta assigners and heads showing morpho-phonologically overt agreement, when the two interact with the same argument DP. This structural generalization bears directly on the proper modeling of syntactic agreement, as well as the prospects for reducing other syntactic (and syntacto-semantic) dependencies to the same underlying mechanism. (This work began as Section 7 of the unpublished manuscript "Agreement and semantic concord: a spurious unification" – see separate entry, below – but has now been expanded into a standalone squib.) -

m-merger as relabeling: a new approach to head movement and noun-incorporation

- download poster; presented at the 40th GLOW (Generative Linguistics in the Old World) Colloquium, and at the Workshop in Honor of David Pesetsky’s 60th Birthday

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@unpublished{LevinPreminger:2017, Author = {Levin, Theodore and Preminger, Omer}, Note = {Poster presented at the {{\em{40th {Generative} {Linguistics} in the {Old} {World} ({GLOW}) Colloquium}}}}, Title = {m\mbox{-merger}} as relabeling: A new approach to head movement and noun-incorporation}, Url = {http://tinyurl.com/dp60lp}, Year = {2017},We propose a modification of Matushansky's (2006) syntactic approach to head movement. The modification has two main advantages, one conceptual and one empirical. The original Matushansky proposal treats X-to-Y head movement as movement of X to [Spec,Y], followed by m‑merger of X and Y. The latter operation is problematic on two fronts. First, it constitutes an interleaving of morphology within syntax. More importantly, it takes what was not previously a constituent – X and Y, to the exclusion of the material in [Compl,Y] – and turns it into something that behaves as a constituent, as far as subsequent syntactic operations are concerned. Outside of head movement, such manipulation of syntactic constituency is unheard of. We propose, instead, that the readjustment embodied by Matushansky's m‑merger happens not at the level of constituency, but in the labels that X and Y bear. Empirically, this allows us to explain why it is that – in any given language – the licensing conditions on reduced nominals (bare nouns, D‑less NPs, etc.) are always at least as stringent as those that apply to full-fledged DPs. These more stringent licensing conditions often include adjacency (as in cases of incorporation and pseudo-incorporation), which our proposal derives as a specific case of a general linearization schema for heads with the kind of complex labels formed by m‑merger. -

Split ergativity is not about ergativity (with Jessica Coon)

- download manuscript; published in 2017, in The Handbook of Ergativity, ed. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam & Lisa Travis, 226‑252. Oxford: Oxford University Press

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@incollection{CoonPreminger:2017, Address = {Oxford}, Author = {Coon, Jessica and Preminger, Omer}, Booktitle = {The Handbook of Ergativity}, Editor = {Coon, Jessica and Massam, Diane and Travis, Lisa}, Publisher = {Oxford University Press}, Title = {Split ergativity is not about ergativity}, Pages = {226--252}, Year = {2017}}It has been frequently noted in the literature on ergativity that few (if any) ergative systems are purely ergative. Rather, many ergative languages exhibit a phenomenon known as "split ergativity" in which the ergative pattern is lost in certain parts of the grammar. The central argument put forth in this paper is that split ergativity is epiphenomenal, and that the factors which trigger the appearance of such splits are not limited to ergative systems in the first place. In both aspectual and person splits, we argue, the split is the result of a bifurcation of the clause into two distinct case/agreement domains; this bifurcation results in the subject being, in structural terms, an intransitive subject. Since intransitive subjects do not appear with ergative marking, this straightforwardly accounts for the absence of ergative morphology in those cases. But crucially, such bifurcation is not specific to ergative-patterning languages; rather, it is obfuscated in nominative-accusative environments because, by definition, transitive and intransitive subjects pattern alike in those environments, and the terminology in question ('ergative' vs. 'non‑ergative') specifically tracks the behavior of subjects. Thus, the tendency noted above does not reflect any deep instability of ergative systems, nor a real asymmetry between ergativity and accusativity. In an ergative system that exhibits this type of split, ergative-absolutive alignment is always associated with a fixed set of substantive values (e.g. perfective for aspectual splits, 3rd person for person splits). The account we present derives this universal directionality of splits by connecting the addition of extra structure to independently attested facts: the use of locative constructions in progressive and non-perfective aspects (Bybee et al. 1994, Laka 2006, Coon 2013), and the requirement that 1st and 2nd person arguments be structurally licensed (Bejar & Rezac 2003, Preminger 2014). -

How can feature-sharing be asymmetric? Valuation as UNION over geometric feature structures

- download manuscript; published in 2017, in A Pesky Set: Papers for David Pesetsky, ed. Claire Halpert, Hadas Kotek & Coppe van Urk, 493‑502. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@incollection{Preminger:2017, Address = {Cambridge, MA}, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Booktitle = {A {Pesky} {Set}: Papers for {David} {Pesetsky}}, Editor = {Halpert, Claire and Kotek, Hadas and van Urk, Coppe}, Pages = {493--502}, Publisher = {MITWPL}, Title = {How can feature-sharing be asymmetric? {Valuation} as union} over geometric feature structures}, Year = {2017}}In this paper, I review two recent developments in the theory of syntactic agreement – feature sharing, and feature-geometric agreement – along with brief synopses of the kinds of facts that have motivated each of the two. I then present an apparent puzzle that arises when these two results are juxtaposed with one another: given that a complete lack of values is itself a valid phi-featural representation (viz. 3rd person singular), why would feature-sharing consistently choose the more marked of its two operands as the output of the sharing operation? I propose a solution in terms of a UNION operation, defined not over sets, but over feature-geometric representations of the kind put forth by Harley & Ritter (2002) and others. -

Agreement and semantic concord: a spurious unification (with Maria Polinsky)

- download manuscript; note: a more up-to-date version of this work is now available here

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@unpublished{Preminger:2015, Address = {Storrs, CT}, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Note = {Paper presented at the {University} of {Connecticut} Linguistics Colloquium}, Title = {Upwards and onwards}, Url = {https://omer.lingsite.org/files/Preminger-Upwards-and-onwards.pdf}, Year = {2015}} @unpublished{PremingerPolinsky:2015, Author = {Preminger, Omer and Polinsky, Maria}, Note = {Ms.}, Title = {Agreement and semantic concord: a spurious unification}, Url = {https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/002363}, Year = {2015}}This work is a much expanded version of Preminger 2013 (TLR), arguing against the spate of recent proposals aiming to reverse the direction of the formal operation underlying agreement in phi-features. We contend that these proposals are an outgrowth of a reasonable -- but ultimately, ill-fated -- urge to reduce any and all correspondence between two elements (be it agreement, or semantic concord) to the same underlying operation. In other words, they constitute a spurious unification. We focus here on Bjorkman & Zeijlstra's (2014) recent "hybrid" proposal -- which is, in title, an attempt to argue for the reversal of agreement, but which sanctions both directions of agreement under different sets of circumstances, for the sake of unifying phi-feature agreement with semantic concord. First, we address instances where Bjorkman & Zeijlstra attempt to argue from data that, upon closer inspection, fail to distinguish regular from reverse agreement. These include fully local agreement (in Bantu), whose irrelevance to the debate was already noted in Preminger 2013; and agreement asymmetries between SV and VS word orders. Next, we address long-distance agreement (LDA) in Tsez and in Basque, the two empirical domains put forth in Preminger 2013 as challenges to reverse agreement. Bjorkman & Zeijlstra attempt to reanalyze these two domains within their hybrid system. We present empirical and conceptual arguments against their analysis. We then review further crosslinguistic evidence demonstrating the same basic point: that a reversal in the direction of agreement is empirically unsupported. Finally, we argue that even if it were successful, Bjorkman & Zeijlstra's proposal would not have achieved what such a unification sets out to achieve: a reduction in the amount of machinery required in the overall theory. Instead, they have to propose several principles which overgenerate and make incorrect predictions. -

Nominative as no case at all: an argument from raising-to-accusative in Sakha (with Jaklin Kornfilt)

- download manuscript; published in 2015, in the Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL 9), MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 76, ed. Andrew Joseph & Esra Predolac, 109‑120. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@inproceedings{KornfiltPreminger:2015, Address = {Cambridge, MA}, Author = {Kornfilt, Jaklin and Preminger, Omer}, Booktitle = {Proceedings of the 9th {Workshop} on {Altaic} {Formal} {Linguistics} ({WAFL} 9)}, Editor = {Joseph, Andrew and Predolac, Esra}, Number = {76}, Pages = {109--120}, Publisher = {MITWPL}, Series = {MIT Working Papers in Linguistics}, Title = {Nominative as \emph{no case at all}: An argument from raising-to-acc} in {Sakha}}, Year = {2015}}In this paper, we present a novel argument that the proper grammatical representation of cases like nominative and absolutive – and, potentially, genitive – is as the *absence* of otherwise assigned case. This contrasts with a positively-specified view of, e.g., nominative, where it is actively "assigned" by the grammar (e.g. Chomsky 2000, 2001). This result provides further evidence that the assignment of case is not a consequence of agreement (see Bobaljik 2008, and Preminger 2011, 2014). The argument is based on raising-to-accusative constructions in Sakha (Turkic). -

Case in Sakha: are two modalities really necessary? (with Ted Levin)

- download manuscript; published in 2015, Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33(1): 231‑250. doi: 10.1007/s11049-014-9250-z

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{LevinPreminger:2015, Author = {Levin, Theodore and Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.1007/s11049-014-9250-z}, Journal = {Natural Language \& Linguistic Theory}, Number = {1}, Pages = {231--250}, Title = {Case in {Sakha}: Are Two Modalities Really Necessary?}, Volume = {33}, Year = {2015}}Baker & Vinokurova (2010) argue that the distribution of morphologically observable case in Sakha (Turkic) requires a hybrid account, which involves recourse both to configurational rules of case assignment (Bittner & Hale 1996, Marantz 1991, Yip, Maling & Jackendoff 1987), and to case assignment by functional heads (Chomsky 2000, 2001). In this paper, we argue that this conclusion is under-motivated, and present an alternative account of case in Sakha that is entirely configurational. The central innovation lies in abandoning Chomsky's (2000, 2001) assumptions regarding the interaction of case and agreement, and replacing them with Bobaljik's (2008) and Preminger's (2011, 2014) independently motivated alternative, nullifying the need to appeal to case assignment by functional heads in accounting for the Sakha facts. -

Agreement and its failures

- 2014. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs 68. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@book{Preminger:2014, Address = {Cambridge, MA}, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Number = {68}, Publisher = {MIT Press}, Series = {Linguistic Inquiry Monographs}, Title = {Agreement and its failures}, Year = {2014}}In this monograph, I show that the typically obligatory nature of predicate-argument agreement in phi-features (person, number, and gender/noun-class) cannot be captured using a model based on "derivational time-bombs." In such a model, there are elements of the initial syntactic representation that cannot be allowed to persist in the final, end-of-the-derivation structure, and it is the application of agreement that eliminates these elements from the representation. (This includes, but is not limited to, the 'uninterpretable features' of Chomsky 2000, 2001.) Instead, an adequate model of phi-agreement requires recourse to operations as primitives – operations whose invocation is obligatory, but whose successful culmination is not enforced by the grammar. I also discuss the implications of this conclusion for the analysis of dative intervention. This leads to a novel view of how case assignment interacts with phi-agreement, and furnishes an argument that both phi-agreement and so-called "morphological case" must be computed within the syntactic component proper. Finally, I survey other domains where the empirical state of affairs proves well-suited for the same operations-based logic: Object Shift, the Definiteness Effect, and long-distance wh-movement. This work is based on data from the K'ichean branch of Mayan (primarily from Kaqchikel), as well as from Basque, Icelandic, French, and Zulu. -

The role of case in A-bar extraction asymmetries: evidence from Mayan (with Jessica Coon & Pedro Mateo Pedro)

- download manuscript; published in 2014, Linguistic Variation 14(2): 179‑242. doi: 10.1075/lv.14.2.01coo

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{CoonMateoPedroPreminger:2014, Author = {Coon, Jessica and Mateo Pedro, Pedro and Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.1075/lv.14.2.01coo}, Journal = {Linguistic Variation}, Number = {2}, Pages = {179--242}, Title = {The Role of Case in \mbox{A-bar} Extraction Asymmetries: Evidence from {Mayan}}, Volume = {14}, Year = {2014}}Many morphologically ergative languages display asymmetries in the extraction of core arguments: while ABS arguments (transitive objects and intransitive subjects) extract freely, ERG arguments (transitive subjects) cannot. This has been labeled "syntactic ergativity" (see, e.g., Dixon 1972, 1994; Manning 1996). These extraction asymmetries are found in many languages of the Mayan family, where in order to extract transitive subjects (for relativization, focus, or interrogative-formation), a particular construction known as Agent Focus (AF) must be used. Crucially, other Mayan languages – though still morphologically ergative – exhibit no such extraction restrictions. In this paper, we offer a proposal for (i) why some morphologically ergative languages exhibit extraction asymmetries, while others do not; and (ii) how the AF construction in Q'anjob'al (Mayan) circumvents this problem. We adopt recent accounts which argue that ergative languages vary in the locus of ABS case assignment (Aldridge 2004, 2008; Legate 2002, 2008), and propose that the same variation is attested within the Mayan family itself. Based primarily on comparative data from Q'anjob'al and Chol, we argue that the inability to extract ERG arguments does not reflect a problem with properties of the ERG subject itself, but rather reflects locality properties of ABS case assignment in the clause. We show how the AF morpheme -on circumvents this problem in Q'anjob'al by assigning case to the internal argument. -

The absence of an implicit object in unergatives: new and old evidence from Basque

- download manuscript; published in 2012, in Lingua 122(3): 278‑288. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2011.04.007

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{Preminger:2012, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.1016/j.lingua.2011.04.007}, Journal = {Lingua}, Number = {3}, Pages = {278--288}, Title = {The absence of an implicit object in unergatives: New and old evidence from {Basque}}, Volume = {122}, Year = {2012}}Basque unergatives have long been held as evidence that unergative verbs have implicit objects (Bobaljik 1993, Hale & Keyser 1993, Laka 1993, Levin 1983, Ortiz de Urbina 1989, Uribe-Etxebarria 1989). Recently, it has been shown that the presence of absolutive agreement-morphology in Basque is not a reliable indicator of a successful agreement relation with a nominal target (Preminger 2009, LI). Building on this, I present two new arguments (and one old one) that Basque unergatives *lack* an implicit object. Since the subject of these verbs is nonetheless ergative-marked, these facts furnish an argument against a case-competition account of ergative case in Basque (i.e., against ergative being a dependent case; Marantz 1991). At first glance, this seems to favor an account of ergative as inherent case. However, previous work on Basque provides evidence against such an account: (i) raising-to-ergative constructions (Artiagoitia 2001), and (ii) the existence of ergative-marked arguments that are unambiguously Themes (Etxepare 2003, Holguín 2007, among others). These facts thus point to the need for a new theory of ergative case that is compatible (at the very least) with:- the existence of ergative noun-phrases without a case-competitor

- the assignment of ergative case in non-thematic positions

- a lexically-determined distinction between unergatives and unaccusatives

I conclude by discussing what such a theory of ergative case might look like. -

Asymmetries between person and number in syntax: a commentary on Baker’s SCOPA

- download manuscript; published in 2011, Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29(4): 917‑937. doi: 10.1007/s11049-011-9155-z

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{Preminger:2011, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.1007/s11049-011-9155-z}, Journal = {Natural Language \& Linguistic Theory}, Number = {4}, Pages = {917--937}, Title = {Asymmetries between person and number in syntax: A commentary on {Baker}'s {SCOPA}}, Volume = {29}, Year = {2011}}This paper is a commentary on Baker's "When Agreement is for Number and Gender but not Person." In many contexts, the behavior of person agreement departs from that of number and/or gender agreement; the central hypothesis advanced by Baker (2011) – the Structural Condition on Person Agreement (or SCOPA) – is an attempt to derive these departures from a single, structural condition on the application of person agreement. In this commentary, I explore Basque data which demonstrates that SCOPA is overly restrictive, as well as a handful of other empirical patterns that SCOPA fails to address but which I believe should be treated as part of the same empirical landscape. I propose an alternative to SCOPA, one which is able to handle these additional patterns, and proceed to show how it can be derived from the assumption that person and number phi-probes are situated in consecutive but separate heads along the clausal spine (Preminger 2009, 2011, building on Anagnostopoulou 2003, Bejar & Rezac 2003, Shlonsky 1989, Sigurdsson & Holmberg 2008, Taraldsen 1995, and others). -

Transitivity in Chol: a new argument for the Split VP Hypothesis (with Jessica Coon)

- download handout of talk @ LSA Winter Meeting (talk given on January 8th, 2011)

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@inproceedings{CoonPreminger:2011, Address = {Amherst, MA}, Author = {Coon, Jessica and Preminger, Omer}, Booktitle = {Proceedings of the 41st meeting of the {North} {East} {Linguistic} {Society} ({NELS} 41)}, Editor = {Fainleib, Lena and LaCara, Nick and Park, Yangsook}, Publisher = {GLSA}, Title = {Transitivity in {Chol}: A New Argument for the \mbox{Little-\textit{v}} {Hypothesis}}, Year = {2011}}In this paper, we provide a new argument in favor of the Split-VP Hypothesis (Bowers 1993, Chomsky 1995, Collins 1997, Kratzer 1996, inter alia), also known as the Little-v Hypothesis -- the idea that external arguments are base-generated outside the syntactic projection of the stem (i.e., outside of VP proper). More specifically, the hypothesis is that external arguments are base-generated in the specifier of a projection which:- endows the stem with its categorial status as verb

- assigns structural Case to the complement of V

- assigns the external theta-role to the subject

While our argument shares some similarities with the one put forth by Kratzer (1996), the data we examine here establishes more directly that these three properties are intrinsically interrelated. -

Nested interrogatives and the locus of [wh]

- download manuscript; published in 2010, in The Complementizer Phase: subjects and operators, ed. E. Phoevos Panagiotidis, 200‑235. Oxford: Oxford University Press

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@incollection{Preminger:2010, Address = {Oxford}, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Booktitle = {The {Complementizer} {Phase}: Subjects and Operators}, Editor = {Panagiotidis, E. Phoevos}, Pages = {200--235}, Publisher = {Oxford University Press}, Title = {Nested Interrogatives and the locus of \emph{wh}}, Year = {2010}}Most of the literature on utterances with multiple-wh constructions is concerned with examples like (1), where more than one wh-phrase is involved in a single interrogative structure: (1) English:

- Who

- ate

- what?

There is, however, a second way in which multiple wh-elements can interact – namely, when one question is embedded within another question: (2) Hebrew:

∼’What is the thing x such that Dan forgot who ate x?'(lit.: ‘What did Dan forget who ate?’) Unlike (1), which is a questions about pairs (namely, pairs of <eater, eatee>), (2) is a question about singletons (only an eatee). The question about an eater is embedded within the larger question, and interrogation regarding the eater is not directly part of the matrix speech-act in (2). I refer to the kind of constructions exemplified by (2) as nested interrogatives. I use the behavior of nested interrogatives in Hebrew, with respect to phenomena such as superiority and syntactic islandhood, to argue that overt displaced wh-elements in Hebrew occupy a position *lower* than the overt complementizer (the C head), whereas intermediate wh-movement crucially involves a position *higher* than the complementizer. As a result, Hebrew appears at first glance to massively violate the "wh-Island Condition." More subtle investigation, however, reveals that this condition – conceived of as a ban against two (or more) elements passing through the position above the complementizer in the same clause – is still operative, even in Hebrew, and a lower final landing site for wh-elements simply makes its effects harder (but crucially, not impossible) to detect.- et

- ACC

- ma

- what

- Dan

- Dan

- šaxax

- forgot.PAST(3sg.M)

- [mi

- who

- axal]?

- ate.PAST(3sg.M)

-

Breaking agreements: distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures

- download manuscript; published in 2009, Linguistic Inquiry 40(4): 619‑666. doi: 10.1162/ling.2009.40.4.619

bibtexhidedescriptionhide@article{Preminger:2009, Author = {Preminger, Omer}, Doi = {10.1162/ling.2009.40.4.619}, Journal = {Linguistic Inquiry}, Number = {4}, Pages = {619--666}, Title = {Breaking agreements: distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures}, Volume = {40}, Year = {2009}}In this paper, I propose a novel way to distinguish between "pure" agreement and clitic doubling. The innovation lies in examining what happens when the relation in question fails to obtain: Given a scenario where the relation R between an agreement-morpheme M and the corresponding full noun phrase F is broken – but the result is still a grammatical utterance – the proposed diagnostic supplies a conclusion about R as follows:- if M shows up with default phi-features (rather than the features of F) → R is agreement

- if M disappears entirely → R is clitic doubling